S2E6 Maine Food System and the Pandemic: Interview with JG Malacarne and Jason Lilley

This episode covers an article in Maine Policy Review by JG Malacarne, Jason Lilley, and Nancy McBrady, entitled “The Response of the Maine Food System to the onset of the Covid-19 Pandemic,” which argues that reflecting on how the Maine food system weathered shocks early in the pandemic can help us prepare for future crises.

Eric Miller: The early days of the Covid-19 pandemic quite literally shocked the Maine food system economically affecting many individuals and sectors in different but interconnected ways. Many households, budgets were disrupted as people lost income, which led to acquiring food in two different ways, all while concerned over the availability of certain products.

Maine food producers faced multiple stressors as the demand for food at home rose, the restaurant market disappeared, and the availability of labor and the tourist market became uncertain. In response to these shocks, policymakers were forced to innovate and adapt in order to support farms, protect consumers, and ensure the food security of the people in Maine.

What can we learn from these shocks of those early days of the pandemic in order to help food consumers, producers, and policymakers deal with the next big shock? This is the Maine Policy Matters podcast from the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center. I’m Eric Miller, Research associate at the center. On each episode of Maine Policy Matters, we discuss public policy issues relevant to the state of Maine.

Today we will be covering JG Malacarne, Jason Lilley, and Nancy McBrady’s Maine Policy Review article entitled “The Response of the Maine Food System to the Onset of the Covid-19 Pandemic”, which argues that reflecting on how the Maine food system weathered shocks early in the pandemic can help us prepare for future crises.

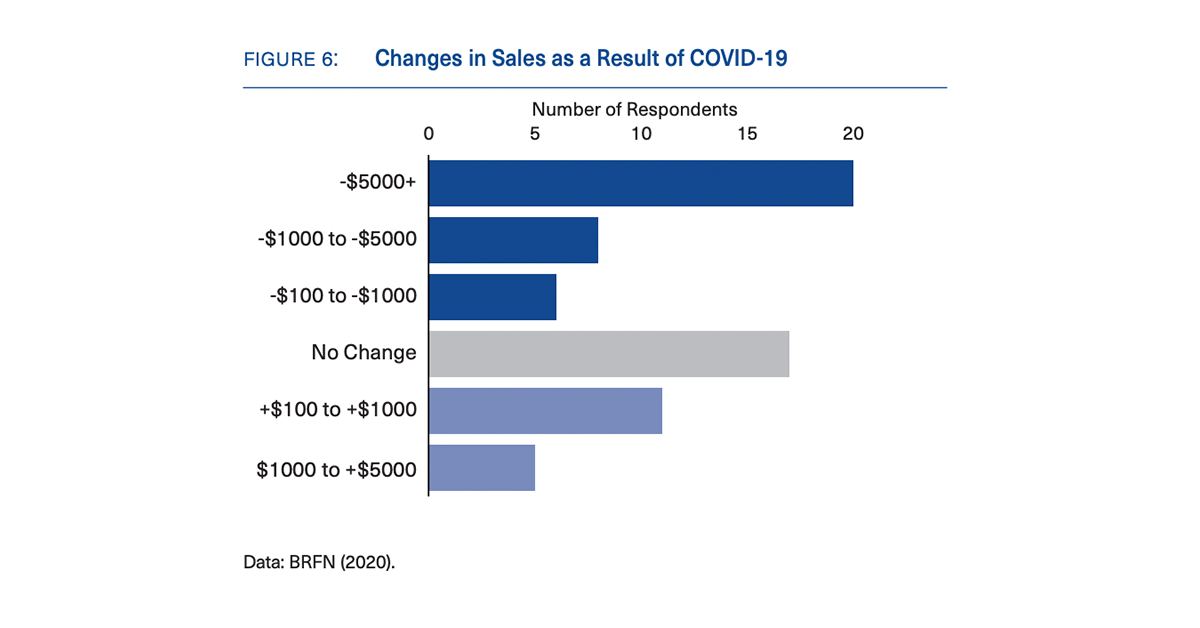

This article was published in Volume 30 number two of Maine Policy Review, a peer-reviewed academic journal published by the center. We will first briefly summarize that article and then speak directly with Dr. Malacarne, Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Maine, and Jason Lilley, Assistant professor of sustainable agriculture and maple industry educator at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension about where the food system is now, two years later, and what the future of food in Maine might look like. Malacarne, Lilley, and McBrady offer data on how the pandemic shocked consumers, food producers, and policymakers in different ways. For example, before the pandemic, Maine was already the most food-insecure state, and the pandemic made this issue worse.

Food insecurity in Maine rose to 14.6% in 2020, compared to 12.4% in 2019. This rise was not related to the unavailability of food, but rather the surge in unemployment and underemployment during the pandemic’s early days. Food distribution outlets thus increased their efforts. Good. Shepherd Food Bank of Maine, for example, distributed 31.7 million meals during the first year of the pandemic as part of the USDA’s Farmers to Families Food Box Program.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP waived their three month eligibility limit and made it easier for applicants to apply, update, and use their benefits with the pilot programs for online food purchasing. To help curb food insecurity, the USDA announced the Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer Program, which allowed households with children facing school closures to access resources through the state’s EBT card system.

During the early pandemic, there was also a rise in the demand for local products. Hannaford reported that purchases from Maine vendors went up by 33.5% in March 2020 compared to March 2019. Local vendors were partly able to meet this demand via direct to store deliveries and safe direct to consumer sales.

Maine farmers, however, also experienced challenges that complicated their ability to plan for this growing demand, such as, as Malacarne et al. wrote: “The disappearance of the restaurant market restrictions on face-to-face marketing and extreme uncertainty about labor availability and the tourist market. To help address this issue, a farmer led effort led to the creation of the main farm in seafood directory, which opened on March 19th, 2020.”

By the end of March, 337 farms and seafood vendors listed their operations and available products on the directory. In under a month, the directory received 47,000 views by consumers who were interested in safe, local, and direct shopping. At the end of September of 2020, the Maine Farm and Seafood Directory had gathered 483 farmers, fishermen, and other producers, and received 91,910 views.

What did consumers and farmers alike learn from the pandemic in these shifts and how do we move? Malacarne et al. conclude their article with two points. The first is the vital need for investments in agricultural storage, processing, and packaging infrastructure in the state. The second is the need for packaging and processing infrastructure to be flexible enough to shift across the restaurant, institutional, and consumer-facing markets.

Having the ability to shift markets when needed will be more sustainable and effective. Malacarne et al. conclude: “Resilient systems include a measure of flexibility and redundancy. Maine can maintain, even enhance its integration into the broader food system while increasing the prominence of its own agricultural products by investing in local agricultural infrastructure, Maine can provide market opportunities to its producers, increase the reliability of the supply of important stable goods for its consumers, and provide sources of employment and income to its workforce. Now we will be talking with Malacarne and Lilley about what the future of the Maine food system might look like.

Thank you both so much for joining us today.

Jonathan Malacarne: It’s my pleasure. Thanks for having us.

Jason Lilley: Thanks for having us.

Eric Miller: Before the pandemic, what aspects of the main food system are unique strengths and weaknesses relative to other states? Has the pandemic and other shocks changed these attributes at all? And if so, how?

Jason Lilley: So I’ll jump in on that one. I would say that from the farmer perspective, the production side of things, Maine has really been ahead of the game and has had a leg up in relationship to the diversity of production types here in the state. So there’s a lot of different types of agricultural production that happen.

And not all, but a lot of that agricultural production is marketed through local channels. So there’s a lot of good relationship building that happens between the clients and, and or the consumers and the farmers as well as loyalty on the consumer’s part to either specific farms or to just supporting the Maine food system as a, as a whole. And I’ve spoken with many folks from the Ag Service provider network, so people from Cooperative Extension and various organizations. And it, it really is a kind of out-of-state Maine is really known for the style of agriculture that we have.

Jonathan Malacarne: I think that’s a great description of some of the strengths on the, on the challenges side and moving a little bit to kind of viewing it through the consumer’s eyes. Maine’s a very rural state. People are pretty spread out and in certain parts of Maine, one of the challenges is the distance to places to go and buy food. It’s often hard to support traditional grocery stores in areas with low population density, and that means that you either have to travel farther to buy food or you have a more limited set of options from which you can buy food, and maybe you need a car to get there. and so as particularly for vulnerable populations, both of those can can make it hard to access food, even if food exists and is offered at an affordable price somewhere.

Eric Miller: Yeah, those excellent insights. It reminds me of a couple of facets of Maine in terms of social relationships in that it’s like a big small town in that you can get to know everyone, but at the same time you can’t get there from here. So it’s going to be a struggle to maintain the supply chain connectivity. And both of those strengths and weaknesses are reflected there, and that’s really, really interesting to me. You suggest in your article that there’s a need for investment in agricultural storage processing, and packaging infrastructure in Maine. You also stress the need for packaging and processing infrastructure to be flexible enough to shift across restaurant institutional and consumer-facing markets.

Have you noticed any evidence of these shifts occurring in Maine over the past two years?

Jonathan Malacarne: Yeah, I’ll start. So I think the first thing to note is that these are really long-term issues. And while it feels like a lot of time has passed in terms of infrastructure changes, we’re still very much in the early stages of making use of what we learned during the pandemic.

At the same time, I think there has been some great movement In infrastructure investment both on kind of through private sources, farm businesses, realizing what they need and starting to make those changes as well as support from, from the state through access to grants. I think we’re just finishing up the Department of Ag Conservation and Forestry administering about $19 million in grant funding specifically for increases in processing infrastructure on farm businesses.

I believe they made 64 grants totaling just under $19 million—that finalized maybe this past month. And so it’s great to see that happening. And it’s also important to acknowledge that that’s really just the tip of the iceberg. In terms of needs for infrastructure investment, there were many, many more applicants proposing much-needed upgrades to the system and to their own operation that remain to be funded in the future. So definitely moving in the right direction, but it’s a slow process.

Jason Lilley: Adding a little onto the Ag Infrastructure Investment program that Jonathan was mentioning, those 60 some awardees they were awarded the grant funds due to the strong agreement and plans to build out the infrastructure on their farm in a way that would help with distribution and processing, not only for their own farm, but for other farms that they’re collaborating with. Or other farms in, in the network with, you know, similar types of production. So that was, yeah, really exciting to see.

That’s gonna have some huge impacts. That’s anywhere between 250 and $500,000 per awardee. And as Jonathan, I was also mentioning there were almost 800 applicants. So that really from my perspective shows the immense amount of need for additional funding into these types of improvements.

Eric Miller: Yeah. On one hand, it’s very encouraging to get so much interest and the fact that this kind of programming and funding is, is, is rolling. But yeah, the, it definitely highlights the, the, the need which hopefully will be addressed as soon as, as feasibly possible, whether it’s through the state, federal programming, what have you.

So can you talk a bit about the consumer demand for local food markets? Uh, is that demand still increasing? What progress and or setbacks has the local food market faced since you wrote this article?

Jason Lilley: So, in my role with Cooperative Extension, I spend a lot of time driving around visiting farms, primarily in the southern part of the state. And one of the, as mentioned in the article, one of the big benefits, I guess, of the pandemic was this big turn towards local food and a huge amount of interest. And um, that has really carried over for the majority of producers. So not only have they built relationships with local people in their communities.

Um, but now the restaurants have started open back up and are really trying to, to, to push hard to support local businesses and all that.

Jonathan Malacarne: Like Jason mentioned earlier, Maine has long had a strong consumer demand and strong consumer interest in local food. And I think that that has continued for lots of people and for, for lots of you know, businesses that make it their goal to provide food that matches well with what consumers want. But now, like always it’s not everyone and it’s not a continual upward path. Some shoppers have gone back to previous behaviors. Some businesses have gone back to business as usual.

Others, you know, found that they liked what they were doing. When it came to food procurement during, during the pandemic and consumers have, those consumers have continued to prioritize local purchases, and a lot of businesses as they reopened and recovered, have identified that being more integrated with local producers can be something that differentiates them in the eyes of consumers and have, have really doubled down on that.

Eric Miller: Yeah, it’s really interesting to think about benefits coming out of Covid, but one thing that was really almost like special to see was how much more engagement people had, both what was on their plate and, and how it got there. And I find that to be something that I mean this goes into my, my personal biases, but I’m very happy to see how that transformation happened because prior to Covid, I, you see the grocery shelves and, and most of the calories people were getting were not necessarily from, they were from a longer supply chain. And so it’s nice to see maybe some, some nudging toward engagement with local producers. and a more diverse set of types of food is nice to see.

Jonathan Malacarne: Yeah, I think it’s a little, I know, we all, a lot of us who work in this space and who have these conversations we spend a lot of time you know, being, being happy about that. I think it’s important to, to realize, and this is a point that we make in the article as well, that the goal, especially if we’re talking about resilient food systems, isn’t necessarily to, to make them hyper-local.

Eric Miller: Right.

Jonathan Malacarne: There are lots of things that we can’t produce here, or lots of things that would take many more resources to produce here.

And so don’t actually kind of have that desirable, say, environmental impact or that desirable impact on sustainability broadly that we might think because they’re local. I think the goal is, as you mentioned, to diversify and to really take a little bit more holistic view of the food system and figure out what we can do well here and make sure that we’re doing that. And at the same time recognize that there are many ways to ensure access to affordable, high-quality food for, for everyone. And that involves making use of our resources here, but then also integrating in a smart way to kind of the broader national and global food system.

Eric Miller: This is why I appreciate having folks like you studying this so carefully because it’s so nuanced. There’s no silver bullet solution. It’s not too industrialized nor hyper-localized. So how would you describe the situation that the main food system is in now, two years in the pandemic and at a point where food costs have been rising for various other reasons?

Have any lessons from the early days of the pandemic helped the food system, whether these new shocks?

Jonathan Malacarne: Yeah, so there’s, you know, one of the things that’s more salient now is that We’re always facing, there are always shocks to the food system, the, the pandemic, the early days of the pandemic, especially where a sudden, large, unexpected and kind of unprecedented shock.

What we’re facing now with rising food costs happens repeatedly, right? Food costs go up, food costs go down. and I think that a few things make this different. and consumers have some, some experience now from the pandemic that can help them face rising food costs. And the first is we all have a little bit more practice being flexible.

And so whenever the cost of, I’m an economist, and so I imagine that whenever the cost of one thing goes up, consumers decide whether or not they wants to continue purchasing it or whether they want to switch to a similar, but maybe cheaper or good. and we have a lot of evidence that that’s actually what consumers do.

So I work with a group at the University of Maine and at the University of Vermont that’s part of the National Food Access and Covid research team. and we run some ongoing surveys and rising food prices is one of the questions that we asked about. and so in our most recent survey 62% of respondents reported that the rising food costs has made them alter their behavior.

But then at the same time, there’s a lot of work that’s done, and in particular I’m thinking of the Consumer Food Insights report that runs out of Purdue. That happens at a much, much higher frequency. and they see similar things that consumers are changing their food purchasing behavior in response to rising food price.

But what they find is that some of that is seeking out more sales and discounts, or some of that is swapping between name brands and generic brands. and so it doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s a one-for-one association between rising food prices and rising food expenditure in every household.

And that is not at all to say that rising food prices are not challenging, it’s just that we have a little bit, everybody has a little bit more practice now responding to challenging situations when it comes to procuring food, and so I know that the system itself is dealing with that and is using that experience very wisely. And I’m confident that consumers are doing the same thing.

Jason Lilley: I would say that the farmers who again, have more of a direct to consumer outlet um, have, have been able to maintain those relationships and that. A lot of the early structures that they set up in order to, to market safely in the face of, of Covid.

So their online sales platforms, their increased, you know, newsletters, all of that have really carried over and not only allowed them to continue to market to these new customers, but have allowed, have allowed them to improve their businesses as a whole. So they’ve got better tracking of what they’re producing and what they’re selling and, and what market outlets their products are going through.

So there are a lot of benefits and kind of on-farm lessons learned that are definitely going to be carried over from the perspective of the farmers who sell wholesale and who have less control over their pricing, they’re, this has been a very challenging season. farm inputs have gone up, you know, between 60 and 120%.

So while farmers’ cost of production is going, is essentially doubled their, what they’re getting has, has really not increased at all. I’ve spoken to several farmers who work with some grocery chains and, and they haven’t seen any increase since 2019. So it’s really tough for them to figure out, you know, how they’re gonna continue to make the farm viable if what they’re selling their product for doesn’t match that cost of production.

So that’s a serious hurdle that needs to be addressed.

Eric Miller: Yeah, it’s, it’s fascinating how this, this practice and flexibility has, has carried over. and it’s also, it blows my mind how in the span of two and a half years we have experienced two historic global shocks, One being pandemic and the other, of course being the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

So, to, I, I’m glad you are keeping tabs on how this, how input costs, is changing and negatively affecting folks and how that’s going to shape policy coming up. And so to transition to little policy talk so there are policy initiatives that help support the food system at the onset of the pandemic.

Now that most of those have expired, have there been any new policy initiatives to aid with ongoing food and financial insecurities due the pandemic or even gas price increases? Uh, what kind of food policy do we need at the present moment?

Jason Lilley: Yeah, I think that you know, unfortunately I don’t have any specific, you know, silver bullet policies that would really solve some of these crises.

But I think that, you know, going back to the previous question, my response in that farmers need to get paid more to match the cost of productions is kind of counter to Jonathan’s response of the consumer’s ability to pay for food and, and rising food costs. So I don’t know if, if there is a solution of stipends for food or, you know, offsets for, for the cost of production. I don’t know in what form that would come in, but that is something that does need to be addressed. So.

Jonathan Malacarne: Yeah, this is actually what Jason just highlighted is often at the top of my mind. I teach a class called the Main Farm and Food Economy and we really engage with this directly like this, this challenge of supporting farmers and wanting farmers to get paid for their effort and for the products they produce and the service that they provide. And at the same time, trying to manage the cost of food so that everyone has access to sufficient quantities and qualities of food to live a healthy lifestyle. and it really is, it’s one of those challenging questions to answer and then put on top of that.

You know, having to, to realize and recognize that anything that we do that affects the price of, of fuel or affects the price of chemical inputs, you know, may also have undesirable impacts for, for emissions and for our kind of ongoing needs to address climate change. and all of these things are connected and, and that makes it really hard.

I think it is important to note that, you know, while some of the specific programs and policies that were designed to address needs at the beginning of the pandemic may have expired. There were lots of organizations and lots of uh, departments and divisions within organizations like the USDA that this is just what they do. And supporting, supporting both farmers and supporting consumers has been their mission since long before the pandemic and will continue to be their mission long after the pandemic, as they administer and run programs to support both farmers and food insecure households every day.

And here it’s the same, the same is true here in Maine, right? There are organizations and there are many people who get up and go to work every day. And this is just, this is their job, and we are going through a moment where that’s been a little bit more in the public eye. And I would love that to be true all the time so that we acknowledge their efforts and support funding for their program even when we’re not dealing with a new acute crisis, right? Access to sufficient quantities and quality of food is an ongoing and always pressing need, and as Jason mentioned, supporting farmers is similarly and, and ongoing and always present pressing need and to, to deal with it. We need to pay attention, not just when something new and exciting and big happens, but every day.

Eric Miller: I really appreciate you both entertaining such an easy question to toward the end of the interview here, and I also appreciate how you’re able to communicate these challenges of consumer prices as well as farmer income as that is very, very challenging problem to address. To finish things off, is there anything else you’d like to share about the Maine food system that we haven’t covered already?

Jason Lilley: Yeah, I’ll, I’ll just jump in as kind of a cherry on top here and remind folks of, you know, the scenario we were in at the onset of the pandemic. Everyone was you know, fully stressed out, confused, didn’t know what was going to happen.

And farmers took a moment, you know, pivoted, you know, almost immediately, and, and really worked on figuring out how to continue to support our community and our local economy and our local food systems. And I would argue that they did that in a way that was wildly successful. And, you know, not at I mean definitely at their own expense and risk to their own health.

And you know, it was financially burdensome, but they all stuck with it. And they were, they were here for the state. And now, you know, the tables have kind of turned, like things have kind of leveled off. We’re seeing inflation kind of in our general economy. I’ve heard numbers of eight to 13% for the average American.

Um, and to pair that with farmers, increased cost, cost of productions being, you know, 60 to 120% in increases. So, I think it’s now a moment to, for the, you know, general consumers of Maine to just really kind of step back and think, you know, if we have the means at all, it’s really, it goes beyond just the food that we’re putting on our table. Us taking that effort to support our local farmers has that ripple effect at supporting a whole economy, the ecosystem you know, and our communities. So that’s what I would leave us with.

Jonathan Malacarne: I can’t do better than that, so I’ll give Jason the last word there.

Eric Miller: Yeah, that was very well put. Thank you, Jason, and thank you Jonathan as well for joining us today on Maine Policy Matters.

Jason Lilley: Thank you for the opportunity to be here.

Jonathan Malacarne: Yeah, it was a pleasure. Thanks.

Eric Miller: What you just heard was JG Malacarne’s, Jason Lilley’s, and Nancy McBrady’s perspective from their article, “The Response of the Maine Food System to the Onset of the Covid- 19 Pandemic.” Maine Policy Review is a peer-reviewed academic journal published by the Margaret Chase Policy Center at the University of Maine. For citations for the data provided in this article, please refer to the original article in Maine Policy Review. The editorial team for Maine Policy Review is made up of Joyce Rumery, Linda Silka and Barbara Harrity. Jonathan Rubin directs the policy center. A thank you to Jayson Heim and Kathryn Swacha, script writers for Maine Policy Matters, and to Daniel Soucier, our production consultant.

In two weeks, we’ll be reading a summary of Rob Brown’s article entitled “How to Save Jobs and Build Back Better: Employee Ownership Transitions As a Key to an Equitable Economic Recovery.” We would like to thank you for listening to Maine Policy Matters from the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine.

You can find us online by searching Maine Policy Matters on your web browser. If you enjoyed this episode, please follow us on your preferred social media platform and stay updated on new episode releases. I am Eric Miller. Thanks for listening and please join us next time on Maine Policy Matters.