S2E8 Comparing COVID-19 to the Great London Plague of 1665

This episode of Maine Policy Matters explores Frank O’Hara’s commentary from Maine Policy Review’s special issue on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the article, O’Hara uses historical accounts from a 5-year-old survivor of the London Plague of 1665, Daniel Defoe, to compare the experiences of that plague and the COVID-19 pandemic in the US.

Transcript

The COVID-19 pandemic and the Great London Plague of 1665. What, if anything, do we stand to gain by comparing these two crises?

Actually, quite a bit, according to long-time community and economic development planner, Frank O’Hara. Today, we will be offering statistics and a survivor’s historical account of the Great London Plague of 1665 compared to the COVID-19 pandemic. While these two events may seem unrelated, the way survivors experienced them isn’t all that different.

Welcome to the Maine Policy Matters podcast from the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine. I’m Eric Miller, research associate at the Policy Center. For those of you who tuned in for this season of the show, we are deeply grateful for your attention and we are excited to bring the next season starting January 17th, 2023.

We’ll be bringing in the new year with discussions regarding the lobster industry, opioid crisis, forest resources, and. So we hope that you are as excited as we are for those essays and interviews. Until then, have a safe and happy holiday season and we will be back with you all next year. On each episode of Maine Policy Matters, we discuss public policy issues relevant to the state of Maine.

Today, we will be covering an article by Frank O’Hara titled, “The Great London Plague of 1665 and the US COVID-19 Pandemic Experience Compared.” This article was published in volume 30, number 2, of Maine Policy Review, a peer-reviewed academic journal published by the Policy Center. For all citations for data provided in this episode, please refer to Frank O’Hara’s article in Maine Policy Review.

In the article, O’Hara uses historical accounts from a 5-year-old survivor of the London Plague: Daniel Defoe. Listeners might recognize Daniel Defoe as the author of the novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe also wrote a lesser known novel called A Journal of the Plague Year. This novel is based on Defoe’s childhood experience of the Plague, city records, and his uncle’s diary.

Frank O’Hara uses excerpts from that novel to argue that our current experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic are not that much different from those of people in 1665 London.

At first glance, it would seem that there is little in common between these two plague experiences. How can we compare the mass deaths in the first 18 months of the Great Plague in London, for example, to the 98 percent survival rate of people infected by the coronavirus?

Despite these drastic differences, Frank O’Hara argues that there are similarities in the “human element” that get at what he calls “basic human reactions to crisis” that can teach us some lessons for the current pandemic. The human element of both crises goes beyond the differences in medical understanding, research and distribution systems, and public health infrastructure.

O’Hara identifies ten main similarities between the Great Plague and COVID, which he calls: the Early Rumors, Fears and Complacency, Fleeing to the Country, Quackery, the Economic Collapse, Government Relief Strategies, Government Public Health Strategies, Masks and Cleanliness, Social Division, and Easing Up Too Soon.

Today we’ll be looking at three of these topics: Fleeing to the Country, the Economic Collapse, and Easing Up Too Soon. We’ll start by discussing what O’Hara calls “Fleeing to the Country,” which refers to people’s attempts to leave crowded cities as a way of staying safe.

Dafoe writes in A Journal of the Plague Year:

The richer sort of people, especially the nobility and gentry, thronged out of town with their families and servants in an unusual manner. Nothing was to be seen but wagons and carts, with goods, women, servants, children, and coaches filled with people of the better sort, and horsemen attending them all hurrying away. In all it was computed that 200,000 people were fled and gone.

This type of plague-fueled migration also happened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

New York City, one of the most populated cities in the US, had a net outflow of 100 thousand households in 2020. This means that people were relocating to their summer houses or moving back in with their parents in smaller towns to try and get away from over-populated areas. Maine experienced a real estate boom in 2021 for this exact reason. Recent research from the Brookings Institute has found that “51 of the 88 U.S. cities with a quarter million people or more lost population between July 2020 and 2021.”

In both centuries, migration to the country highlights a class disparity. Wealthy people in both centuries were able to escape once things got bad, a move that not everyone could afford to make.

Relevant to wealth and class disparity is the next section of O’Hara’s article: the Economic Collapse.

O’Hara writes that “here in the United States, the country lost 20 million jobs in April 2020, the largest single-month decline on record. As we’ve covered in previous episodes, the hardest hit sectors were leisure and hospitality, retail, professional services, and manufacturing. This economic collapse is similar to what happened to the economy in London during the plague.

From Dafoe’s journal:

All master-workmen in manufactures stopped their work, dismissed their journeymen and workmen, and all their dependents. As merchandising was at a full stop, for very few ships ventured to come up the river, and none at all went out; the watermen, carmen, porters, and all the poor, whose labour depended upon the merchants, were at once dismissed, and put out of business. All the tradesmen usually employed in building or repairing of houses were at a full stop; so that this one article turned all of the ordinary workmen of that kind out of business, such as bricklayers, masons, carpenters, joiners, plasterers, painters, glaziers, smiths, plumbers and all the labourers depending on such. The seamen were all out of employment, and all the several tradesmen and workmen belonging to and depending upon the building and fitting out of ships, such as ship-carpenters, caulkers, ropemakers, dry coopers, sailmakers, anchor-smiths, and other smiths; blockmakers, carvers, gunsmiths, shipchandlers, ship-carvers, and the like; all or most part of the water-men, lightermen, boat-builders, and lighter-builders in like manner idle and laid by. All families retrenched their living as much as possible, so that innumerable multitude of footmen, serving-men, shop-keepers, journeymen, merchants’ bookkeepers, and such sort to people, and especially poor maid-servants, were turned out, and left friendless and helpless, without employment and without habitation.

Listeners might recognize some similarities from this account of the unemployment and supply chain disruptions that we are currently experiencing. Despite the similarities between the two crises, O’Hara points out that unlike 17th century London, the United States had unemployment insurance to cushion the economic impacts, something that did not exist in 17th century London.

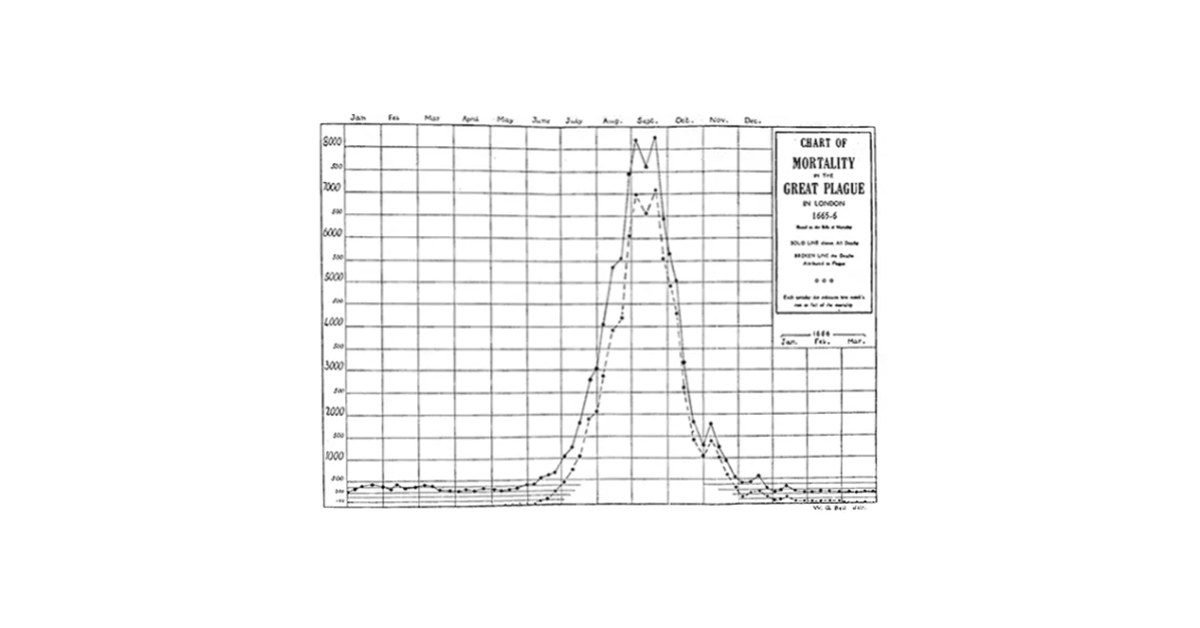

The last section of O’Hara’s article that we will be covering today is Easing Up Too Soon. O’Hara states that, in the summer of 2021 in the United States, we opened up too soon, which allowed the COVID-19 pandemic to reignite through August and September via the new Delta variant. But even with rising numbers of cases and death, governments did not increase restrictions.

Something similar happened in London according to Dafoe:

Upon this notion spreading that the distemper was not so catching as formerly, and that if it was catched it was not so mortal, and seeing abundance of people who really fell sick recover again daily, they took to such a precipitant courage, and grew so entirely regardless of themselves, that they made no more the plague than of an ordinary fever, nor indeed so much…This imprudent, rash conduct cost a great many their lives who had with great care and caution shut themselves up and kept, retired, as it were, from all mankind. A great many that thus cast off their cautions suffered more deeply still, and though many escaped, yet many died. The people were so tired with being so long from London, and so eager to come back, that they flock to town without fear or forecast, and began to show themselves in the streets, as if all the danger was over. The consequences of this was, that the bills increased again 400 the very first week in November.

O’Hara identifies other similarities such as the quackery of Londoners and Americans trying to make at home remedy treatments, the swift relief programs the magistrates of London and America’s federal government pieced together, the ways public health was handled by London officials and the US Centers for Disease Control, and Londoners’ and American’s desires for being done with the crises before they were actually over.

O’Hara concludes his article with a hopeful message and prediction:

There were similar behaviors in both centuries with regard to hating quarantines, falling for quack remedies, and easing restrictions before the pandemic was over. There were also differences. The American response to COVID-19 was much more casual than London’s response to the plague, our social divisions persisted during the pandemic, and oddly doctors in 17th century London appear to have been listened to with more respect than doctors today.

The year after the Great Plague ended, the Great Fire burned the City of London to the ground. Many records were lost, and the plague was forgotten in the rush to rebuild. Had that five-year-old boy not returned to tell the story 50 years later, we would know very little about the plague that wiped out a quarter of London’s population in 1665. Which raises the question—is there a five-year-old child in Maine today who will someday tell of our experiences in 2020 to future generations?

What you just heard was Frank O’Hara’s comparison of the Great London Plague of 1665 to the US COVID-19 Pandemic Experience. Maine Policy Review is a peer-reviewed academic journal published by the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center.

The editorial team for Maine Policy Review is made up of Joyce Rumery, Linda Silka, and Barbara Harrity. Jonathan Rubin directs the Policy Center. A thank you to Jayson Heim and Kathryn Swacha, scriptwriters for Maine Policy Matters, and to Daniel Soucier, our production consultant.

We would like to thank you for listening to Maine Policy Matters from the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine. You can find us online by searching Maine Policy Matters on your web browser. If you enjoyed this episode, please follow us on your preferred social media platform to stay updated on new episode releases.

I am Eric Miller–thanks for listening and please join us next time on Maine Policy Matters.