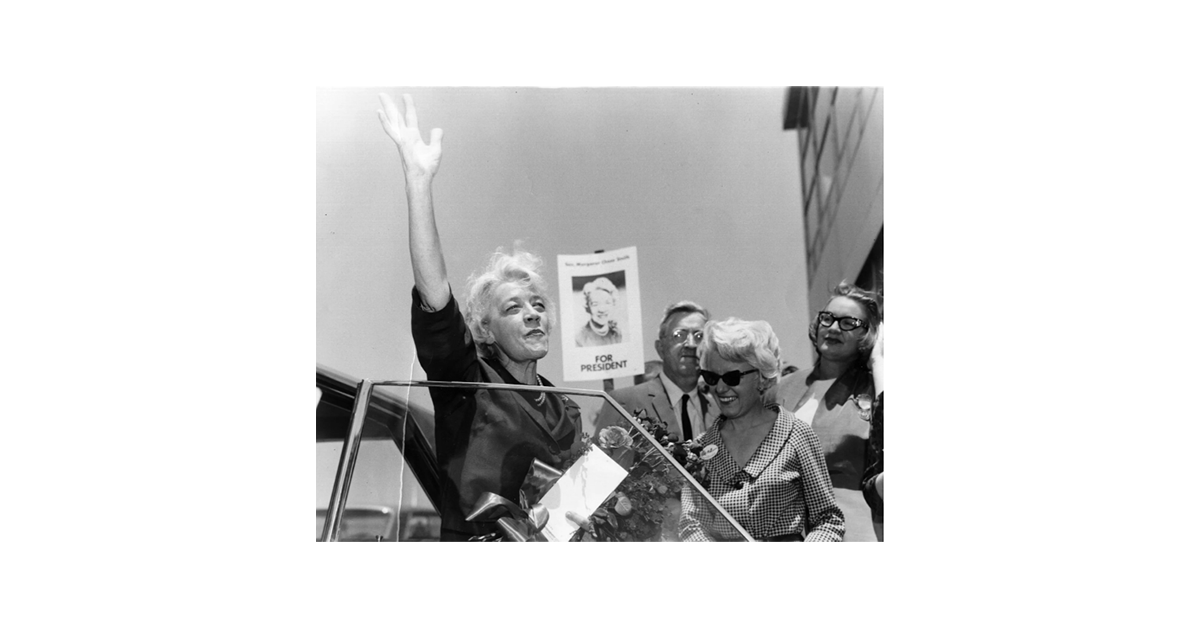

S4E6 Democracy: Margaret Chase Smith and the League of Women Voters

On this episode, we discuss the Maine League of Women Voters, and this organization’s ties to the Margaret Chase Smith Library and most notably, Margaret Chase Smith herself.

First is an introduction by Dr. David Richards, the director of the Margaret Chase Smith Library on Margaret Chase Smith’s lifelong connection to the League of Women Voters, how she won the League’s Carrie Chapman Catt Award, and the significance of this honor. Then we talk with Anna Kellar, executive director of the League Of Women Voters of Maine, about what it truly means to make democracy work, their essay, “What’s In a Name? Being a League of Women Voters in 2022”, and their connection with the Margaret Chase Smith essay series. Kellar’s essay was featured in Volume 31, Issue 1 of Maine Policy Review.

[00:00:00] Eric Miller: Hello, and welcome back to Maine Policy Matters, the official podcast of the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine, where we discuss the policy matters that are most important to Maine’s people and why Maine policy matters at the local, state, and national levels. My name is Eric Miller, and I’ll be your host.

Today, we’ll be talking about the Maine League of Women Voters and this organization’s ties to the Margaret Chase Smith Library, and most notably, Margaret Chase Smith herself. First, we’ll hear a brief introduction written by Dr. David Richards, the director of the Margaret Chase Smith Library, on Margaret Chase Smith’s lifelong connection to the League of Women Voters, how she won the League’s Carrie Chapman Catt Award, and the significance of this honor.

Then we’ll be talking with Anna Keller about what it truly means to make democracy work, their essay, What’s in a Name? Being a League of Women Voters in 2022, and their connection with the Margaret Chase Smith essay series. Keller’s essay was featured in Volume 31, issue 1 of Maine Policy Review. In the words of David Richards:

Although Margaret Chase Smith never belonged to the League of Women Voters, the organization played an important role in her political career. Scrapbooks at the Margaret Chase Smith Library document her having dutifully filled out League of Women Voters candidate questionnaires and having addressed clubs in Bangor, Lewiston, Auburn, and Portland during most election cycles.

Her eventual national prominence also brought her in contact with League chapters in Washington, D. C., Columbia, Missouri, and San Francisco, California. At a pivotal moment in her life, Representative Smith laid out what impressed her about the League of Women Voters. In an address to the Portland Chapter on August 20, 1947, she began by praising the assembled members as, quote, “women who have best accepted their responsibilities as citizens”, end quote.

She went on to list four pillars of that citizenship. The first was the classical Republican ideal of eternal vigilance, necessary to protect democracy from threats. Second was exercising the right to vote, which she reminded listeners was comparatively most recent for women. Third was political awareness, which you define as an interest and intelligence in those matters which vitally affect the basic concepts of a democracy. Fourth was the duty to articulate those concepts to the public. Vigilance and voting, awareness and articulation were the lead up to a final ultimate responsibility to run for office. Representative Smith’s remarks came shortly after she had somewhat surprisingly announced her intention to seek election to the United States Senate.

In a Republican primary that would pit her against three men, two of whom had served as Maine governors, Sumner Sewall and Horace Hildreth, she pointed out that if women would vote in blocks, they would wield majority voting power. She assured her audience that even though females were comparatively new to politics, they possessed vast experience as, quote, “governors of the home,” unquote.

Smith regarded that basic institution is foundational to all other levels of government, local, state, and national. Smith’s call was prescient, and her calculations were accurate. In a four-way primary, she won a majority of the vote without benefit of ranked-choice voting. In the 1948 general election, she easily defeated her Democratic challenger, Adrian Scolten, making her the first woman to serve in both chambers of Congress and the first woman to enter the Senate without first being appointed to the office. Ironically, the welcoming plaque she was presented congratulated Margaret Chase Smith for, quote, “being duly elected by the people of his state,” end quote.

The work for electoral equality was not over 75 years ago, nor is the need for vigilance, voting, awareness, and articulation any less now, as has been made tragically manifest by the political turmoil in Washington over recent weeks. The work of the League of Women Voters to continue cultivating the best responsibilities of citizenship remains as vital today as it was in August of 1947 when Margaret Chase Smith spoke to the chapter in Portland, Maine.

Anna Keller is the Executive Director of the League of Women Voters of Maine. They started working on democracy reform in Maine as an organizer on the 2015 referendum that strengthened the Maine Clean Elections Act. They ran for the state legislature as a clean election candidate in 2016. In 2017, Keller was appointed as the first Joint Executive Director for Maine Citizens for Clean Elections and the League of Women Voters of Maine.

Hi, Anna. Thank you for joining us today.

[00:04:59] Anna Kellar: Thanks for having me.

[00:05:00] Eric Miller: To begin, could you give us some background on your position at the Maine branch of the League of Women Voters and what work this organization does?

[00:05:09] Anna Kellar: I’m the executive director for the League of Women Voters of Maine. Been in that role for about six years now, and I was the first staff person hired in the history of this more than hundred-year-old organization.

So we’ve been in a period of a lot of growth in the last few years here. We do both advocacy to expand voting rights, defend our democracy. We’ve worked on issues around money in politics, rank choice voting, all of these hot button issues around our democracy at the state level. And we also do a lot of work to support voters having the information they need to cast an informed ballot.

We do voter registration. We work with a lot of different community organizations to try to support their civic engagement. So really everything that goes into making our democracy work better for more people from being able to vote all the way up through passing policy.

[00:06:07] Eric Miller: In your 2022 essay for Maine Policy Review, you wrote, quote, “In the last few years, Maine passed the nation’s first statewide ranked choice voting law, strengthened our first in the nation clean elections law, instituted automatic voter registration and online voter registration, and expanded access to absentee voting,” end quote.

Can you explain for our listeners why these successes are so crucial for the League of Women Voters of Maine? And why this work is important, not only for statewide voters, but also on a national scale.

[00:06:40] Anna Kellar: So we’ve been proud in Maine to be a leader on democracy. We were one of the first states to have same day voter registration all the way back in the seventies.

And so we’ve been since then passing our Clean Elections laws in the nineties and then defending them in 2015. We were the first state to have statewide use of rank choice voting. And then since 2020 and the pandemic, what became clear was that while we have really great rights as voters in Maine, what was lagging behind were the systems, that when you looked at the technology, our state elections and local elections had been deeply underfunded and under resourced for a long time.

So while there are great people working in those offices, there were a lot of vulnerabilities when we started looking at the challenges of holding an election under Covid, and things like not having online voter registration started to become a lot more of an issue. And since 2020, we’ve actually been able to achieve a lot.

We now have automatic voter registration. So that’s when you go to the DMV and update your information, get a driver’s license. That’s automatically creating a voter registration update. We also are about to have online voter registration, will go into effect next year. We also were able to expand absentee voting. So now if you are a voter who wants an absentee ballot every election, you’ll be able to sign up for that once, and then it will come every election and so that in 2024 will be available for voters 65 and over or with a disability and then it will eventually go into effect for all voters.

So all of these policies, and there are more, have been things that are bringing Maine’s election system really up to the level of convenience for voters, so that people can be sure to vote and having some, life upheaval, having a day where a family member gets sick or your job calls you out of the state, these are things that happen to people all the time. And that shouldn’t be a reason why they’re not able to exercise their fundamental right to vote. So having all of these more options for voters and more convenience is really helpful.

And I’m excited to see Maine sort of catching up in this space, as well as the places where we’re leading. So in 2022, Maine had the, I think the second highest turnout in the country after Oregon, and we’re always in that top one, two, or three, but when you look at that, there’s still a lot to be done because when you look below the surface of those numbers, you realize that’s in a presidential or a midterm year.

Once you look at off years, it drops. Once you look at local elections, we don’t even have good data about turnout on local elections because it’s so decentralized, but certainly we see that turnout is much lower there typically. And then when you look at different communities, there’s also big disparities.

So one of the pieces of research that we’ve been able to do was to look at voter turnout, house district by house district. And you can see big gaps. So let’s say in 2020, for example. I grew up in Falmouth, voter turnout and found within 2020 was over 86 percent. Where I live now in the middle of Portland and Parkside in that district voter turnout barely hit 50 percent. And the thing is, it maps almost perfectly on to the percentage of voters in the district on food assistance.

And what we start to see is that the places that have the lowest voter turnout are places where people’s lives may be very chaotic. They tend to be places where people are struggling economically, lots more renters, lots more young voters, lots more people who may have a harder time plugging into what’s going on in their community or finding the time to vote.

And also often communities that people don’t really trust that their voice is going to matter. They’re marginalized in a whole bunch of ways in our society and they may not trust that their government is really working for them. And so motivation to vote as well as opportunity can also be lower. So having said all of that, clearly our work is not done.

And I think Maine has this really exciting opportunity for us to say we’ve done a lot of the low hanging fruit things that people push for in terms of voting rights and election administration. So if we’ve done that and we’re not content with where it’s gotten us, it’s been good, but not enough.

Then we get to say what comes next? Are there other policies we should be looking for? What does the kind of community organizing to fill those gaps look like? And so we’re continuing to be leaders in this space. And it’s something that I’m really proud of. And I think we’re a small state. We’re not necessarily representative of every dynamic that’s going on in every state around the country, but because we’re small, sometimes it means makes it easier for us to analyze and get our arms around a problem and bring people together.

So I think we’ve been able to do a lot of really interesting collaborative work in this voting space, and I’m excited about what might come next.

[00:11:58] Eric Miller: Yeah, I feel like every time I talk to someone from outside of Maine and mention ranked choice voting is the thing there, it’s like there and I know San Francisco has a form of ranked choice voting in their elections, and they’re just bewildered that Maine would be the place to push this type of reform and trying to level the playing field for other candidates and make room for more people.

What did you hope people take away from your essay that you wrote for Maine policy review and what motivated you to write it initially?

[00:12:30] Anna Kellar: My essay was asking kind of what we could learn from the League of Women Voters, which like I said, is a hundred year old organization and in a lot of ways, a very old fashioned organization.

How is it relevant in 2022, now 2023? And I was thinking about sort of what’s in a name, and even these organizations that have League in the name, it’s League of Cities or League of Conservation Voters, these, you can tell by that when they were formed, it’s kind of an old-fashioned framing.

But I was thinking about how each of the words in our title of League of Women Voters are contested right now, obviously, who can be a voter and under what circumstances people can vote is deeply contested. We’re seeing around the country that there’s an increase in voter suppression in some places, as well as an expansion in terms of rights restoration and other places.

Who’s a voter? Deeply contested. What does it mean to be a women’s organization? Also deeply contested. And the League has always been kind of interesting in this space because it was founded by women who came right out of the movement to get women’s suffrage. It was actually founded six months before the final ratification of the 19th Amendment with the goal of educating Women voters to be able to fully use the right.

But very quickly there was this understanding that actually all voters needed that education. It wasn’t just women. And so the league has always had this mission of serving the whole population. It’s in a place that has prioritized women’s leadership. And then in our current world, I think that brings up a lot of questions where you can say both women are being politically marginalized in a bunch of ways, there’s absolutely still a need for women’s leadership in politics.

And at the same time, we’re asking what about rights for trans folks? So I’m non binary and I’m the leader of the League of Women Voters in Maine. For us to be able to talk about gender justice in a broader frame is, has been really interesting, and we have this conversation with other organizations that came out of feminist or women’s movements to say in framing things that way, end up excluding people.

And then the other piece of that has been interesting for us is recognizing that actually there are people of any gender who really what we’re doing and want to get involved. And so for us, we’ve been finding, more and more, we have men who are part of the League of Women Voters. And are, working as part of our organization and even taking some leadership roles, and that’s a fantastic thing, too.

So really, it’s about whoever wants to be doing this work, but that we have these roots in being in an organization that came out of a movement to bring rights to people who were being denied them. And so if we can hold on to that part of our origin and think about who is being excluded right now, and how can we be working as allies for them?

I think that part of our history is really important. And like I said, the idea of a league is a little old fashioned, but really where it came from is this idea that you might have grassroots organizations of people coming together with their friends and neighbors saying, this is something that’s important to me. I want to work on it. And then connecting to people in other towns, other states across the country who have the same ideas and coming together in a common project. And I think that idea, when we are often so isolated in some ways and hyper connected in other ways, the idea of what does it look like to really commit to doing a project with a small group of people but in community. Increasingly larger community. I think it’s a really important question for us. It’s something that we think a lot about with trying to build out our local chapters and support them, coordinate at the state level, be part of a national organization. All of these things, like this question of what does grassroots political organization look like right now, I think is also a very kind of hotly contested and difficult to solve question.

So all of these things that might have just seemed set terms we don’t think that much about, when I actually started trying to think about who we are and this name, that sometimes is well known to some people it’s got this reputation. People go Oh, yeah You used to hold the presidential debates back in the day, or you know having this sort of idea of who it is, that can be great for that trust that comes with that long history but it also can mean that people will dismiss us as saying, oh Just those people who did that thing, are they still around?

And so trying to think about how do we use who we are in that legacy to kind of reinvent ourselves and bring forward the things that are relevant to right now. It’s basically what I think about in some form every day, so it was a great opportunity to write the essay and try to put that concretely out into the world.

[00:17:18] Eric Miller: Yeah. Excellent. Very interesting. What has been the strategy to, not necessarily pivot, but broaden and further integrate into various communities around the state of Maine? Have you found that the National League of Women Voters has been on the same type of path and having the same trajectory as you all have?

[00:17:37] Anna Kellar: Yeah. I do see what we’re doing in Maine as being part of a national movement. Trying to figure out how to take what’s best in the League and also change in ways that are not serving us. And so I talked to folks in other states at the national organization about all of this a lot. In some ways, I think we’ve been able to lead on this as well in Maine.

We are a league that has a little more capacity than many. We have seven staff, which goes hand in hand with the all how active we are on policy. And that’s larger than most state Leagues. Only 14 around the country have staff at all, and so we’re in a position to try out a lot of things, even though we’re a small state kind of organizationally as well.

One thing we were able to do was to make our membership be a pay what you can dues model. And so it was really important for us as we were saying we want to be inclusive to not make membership money be a bar for people to be getting involved. Our members vote on policy decisions for us. It’s a really internally democratic model.

And so putting a financial barrier to that did not seem right, even though, of course, like everybody, we depend on those donations and those membership dues to help make our work possible. We tried to take what we’d seen happening in other sectors where if you give people the option of a sliding scale, people will give at their capacity level and some people will give more and that will compensate for the people who have to give less. And we’ve really found that to be the case. So that’s something we’ve been able to share with other Leagues and say, look, this is actually working for us. We’re bringing in new people and it is allowing us to talk to people about joining in a way that is not starting with here, pay your dues, and then you can be a member.

But the biggest part for us about making this transformation has been partnerships. So as we think about where there are gaps in voter turnout, like I was talking about, or communities that are facing particular barriers. What we’ve been finding is that there are already people within those communities who are thinking and working on those issues, of course, but what they often don’t have is the capacity to put a lot of time toward it, the institutional knowledge.

And so what we have often been able to do is provide some technical assistance, whether that be training people and doing voter registration or talking through how a policy process works. We’ve done a lot of work with young people around bill tracking and following legislation that they’re interested in, for example.

We’ve also partnered with housing providers and some immigrant organizations to do some door to door canvassing for voter registration and voter education, and we’ve been able to provide materials and then translate them into a bunch of languages. And as we do that work, we learn more about each other and we learn about what the barriers are and the opportunities are that we might not have known about otherwise.

And so it is making our organization more diverse. But I think what it’s also doing is helping us to recognize that if we are showing up and doing the work and building relationships, whether the people that we’re working with consider themselves members of the League of Women Voters or not, is less important than those relationships and that work that we do together.

And so we’ve also found that the sort of stereotypical League of Women Voters member who is, it’s not an unfair image of who we are, which is a woman in her 60s or 70s, retired, well educated, probably white, probably relatively upper middle class. We have a lot of retired librarians. It’s certainly true about who tends to be coming to work with us.

It’s not, only that, but there’s some truth to it. But what I think we’ve been finding is that with people who are retired and have finished a career, have a lot of knowledge and time on their hands. And if that can be put in the service of building these relationships and working in partnership with people who have their own skills, we find out that everyone has something to teach and everyone has something to learn.

And that the time and the ability to volunteer is itself a privilege. So for our members who have that privilege and can share it, it’s a really valuable thing for them to be bringing as allies and in part of a, broader and more inclusive movement. So that’s one of the things that I’ve loved is watching the intergenerational work and the work that we’ve seen building those relationships and better understanding each other.

[00:22:00] Eric Miller: So pulling out some threads that you’ve had in your answers and accessing less politically active or available populations and marginalized peoples and engaging folks already active in your organization and expanding, why is it important to acknowledge some of those groups that are marginalized or less politically accessible that were potentially formerly excluded from the League, and how does the league now strive for inclusivity and intersectionality? And if you wouldn’t mind speaking to defining inclusivity and intersectionality to provide some of the context.

[00:22:35] Anna Kellar: So the history of the League is as messy in some ways as probably the history of most social movements are that it came out of one part of the suffrage movement. And the women who were involved in it were many of the people who were working on a state by state strategy. They were really focused on trying to pass the right for women to vote in as many states as possible and then secure ratification of the amendment.

And what that meant was that they were looking at what do we have to do in each of these states to make this possible? And a lot of that, unfortunately, was reassuring people that it was going to just be white women, that white women might in fact be a barrier, sort of buffer against the political influence of whether it be immigrant or African American men that there was worries about having political influence.

There was, a lot of those things, and you can find it in the speeches that were made by some of these suffrage leaders. Whether they were themselves thinking that was their political goal or they were being politically expedient to try to get their goals passed. In some ways, it doesn’t matter because the result was that people of color, women of color were really left out of the movement.

And in a lot of ways, the fight for voting reform could also include, at times, it was inclusive of working class women talking about labor issues, talking about a broader set of concerns that women might have. But at other times, because it was led by women who are economically more well off, Their political rights were the primary concern, and so there was less talk about economic rights as well, and so all of those things that as we’ve seen broader social movements and movements for equality around the country through the civil rights movement, through the feminist movement in the 70s, like all the way up to the present day, we’re still asking these questions of what do you push for first?

Whose rights matter more than other people’s rights? If one population is the most at the margins and they’re the ones that are going to be the hardest politically to fight for, do you say, wait your turn? I think all of these questions that we see come up with things like it happens within the Black Lives Matter movement.

I think about the movement for marriage equality in Maine and around the country and this question of do you fight for marriage or do you fight for non-discrimination first? These were questions that people really fought over within, within communities because different members of our community would feel those issues more or less strongly.

And so I think what I take out of all of this is that a, It’s always easy to say to the people who are at the margins, we’ll get to you later, wait your turn. And I think we have to be really cautious whenever we do that. There are sometimes political compromises and you take incremental step forward.

But when that is at the expense of people who are the most vulnerable, should really pause before doing that. And it’s something that comes up, in our politics regularly. Intersectionality, it’s a long word, but I just take it to mean that people have multiple identities that matter to them. Someone might be a Black woman who is disabled, might in some ways be benefiting from reforms that are meant to help all women, but if her other identities and the ways that she’s marginalized in our society aren’t being taken into consideration, there’s a good chance that those policies won’t actually help.

And I think that shows up in so many different ways. We think about how, there’s often this conversation I have with people who really want to see a greater increase of representation of women in politics, for example. And does that mean that you should vote for a woman just because she’s a woman?

Does that mean you should vote for a woman who is supportive of a certain set of feminist policies? What if you think that there’s someone who might actually represent those policies but doesn’t come from that background? These questions are complicated, and when I look at that history… I am compassionate for the choices that the campaigners at the time were making, even though I wish they had made different choices.

And I hope that I’m doing better. I hope that we’re doing better than that. And I also hope that when people look back at us, they have a little bit of compassion for the ways when you’re in the middle of these movements, these choices often are not crystal clear.

[00:27:16] Eric Miller: Yeah, it’s a fascinating from a research perspective, a fascinating, interesting time in, in our history and navigating that as an organization that hopes to uplift and bring people together and successfully advocate for and help pass legislation meant to achieve those ends is something that requires such thoughtfulness and I really appreciate what you’re doing.

As we close out, is there anything else you’d like to discuss about the League of Women Voters that we haven’t already talked about?

[00:27:47] Anna Kellar: One thing that I was thinking about, and this is just to continue on to some of what we were just talking about with the ideas around strategies and tactics and movements, but I was thinking about how during the fight for women’s suffrage in the 19 teens, there was one group that they had the idea that they would convince President Wilson to support women’s suffrage by being supportive of efforts in the First World War.

That’s sort of a, we’ll be on your side so you’ll be on ours. There was another group that said, nope, we’re going to chain ourselves to the gates outside of the White House and we’re going to go on hunger strikes and we’re going to make a fuss and we’re going to be uncomfortable and we’re going to make everyone else uncomfortable around us and that’s how we’re going to get what we need.

And so there was one group, like I said, that was trying to work slowly politically through the states and another group that was trying to be much more radical in their tactics and much more confrontational. And at the time, these two groups hated each other, but you look back on it now and it’s hard to tease out, would it have happened?

It happened the way that it did without both of them. And so that’s something that I also try to remember that, it’s very easy to say, Oh, that tactic is too confrontational that stresses me out to think about having that people be that mad at me if I stand up for this, but I try to have those conversations with our members to say, that’s also in our history and civil disobedience is also in our history. And so when we’re willing to embrace those tactics, we certainly shouldn’t reflexively shame other people who use them in support of their rights and that movements are complicated. It usually takes multiple strategies. And sometimes at the time, those strategies will feel like they’re in opposition, but we have a lot of different tools at our disposal.

And so I try to encourage the League members to think about the ways that we can be brave in the service of our values.

[00:29:47] Eric Miller: Thank you very much for joining us today, Anna.

[00:29:50] Anna Kellar: Thank you for having me and thank you for the opportunity to write the essay.

More information on the League of Women Voters can be found in the description of this episode. Thank you, listener, for joining us. This is Eric Miller and I’ll see you next time on Maine Policy Matters where we’ll be interviewing the University of Maine’s 2023 Student Symposium winners. Our team is made up of Barbara Harrity and Joyce Rumery, co-editors of Maine Policy Review.

Jonathan Rubin directs the Policy Center. Thanks to Faculty Associate Katie Swacha. Professional writing consultant, Maine Policy Matters intern, Nicole LeBlanc, and podcast producer and writer, Jayson Heim. Our website can be found in the description of this episode, along with all materials referenced in this episode, a full transcript, and social media links.

Remember to follow the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads, and drop us a direct message to express your support, provide feedback, or let us know what Maine Policy matters to you. Check out mcslibrary.org to learn more about Margaret Chase Smith, the library and museum, and education and public policy.

See you next time.