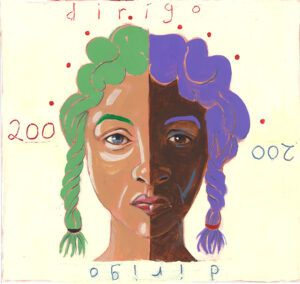

Indigenous Voices Charting a Course Beyond the Bicentennial Eba gwedji jik-sow-dul-din-e wedji gizi nan-ul-dool-tehigw (Let’s try to listen to each other so that we can get to know each other)

by Gail Dana-Sacco

Indigenous languages reflect an understanding of the Universe that recognizes the dynamic energy fundamental to all our relationships. We realize, for instance, that dawn does not happen in an instant, but rather through chqoo-wubg,1 a rhythmic daily process that brings us into light. Chqoo-waban-a-kee-hq, the Indigenous peoples of this area, now known as the state of Maine, hold a cultural framework embedded in our languages that reflects a sophisticated understanding of our intimate and complex connections with all people and with the environment in which we live. Our collective identity as Indigenous people resides here and provides a firm foundation for strong healthy communities. Our relationships extend well before and will persist well beyond Maine’s 200 years.

Indigenous peoples have consistently responded with generosity and diplomacy in our dealings with the state of Maine and with others before them who have failed to treat us respectfully. We persevere, guided by our Indigenous knowledge, despite persistent attempts to colonize our territories and eradicate our people. A Passamaquoddy tribal leader recently observed:

This is Wabanaki territory that we stand on and we still recognize this as our homeland. We always will. We have fished these waterways and protected this land for more than 11,000 years. The Wabanaki people are a resilient people. We have survived despite displacement, sicknesses, poverty, trauma and war. We survived, but we have paid a severe price over many, many generations. No matter what we have endured, we have adapted, and I credit this to our cultural belief systems. Our beliefs are rooted in natural laws, they are rooted in the relationship we have with one another and in our connection to this earth. Our ancestors were always willing to come forward to help, to share, and to be good neighbors. Our sovereignty before the contact with European settlers was much different than it is now. It was unquestioned and respected. We have kept peace despite broken treaties and empty promises. (Dana 2020)

The goal remains establishing an enduring, respectful coexistence that enables all of us to thrive. Restoring peace in our homelands requires that Indigenous voices, repressed and silenced as a direct consequence of the colonial enterprise, be heard and fully engaged across multiple dimensions, in Indigenous languages and in English. The highly endangered state of our languages puts us at risk of irreparable harm. The monumental task of restoring Indigenous-language-speaking communities provides a pathway for healing and an opportunity for redress of harms done. As we reclaim our voices and our language, we collectively experience we-tchqwa-bg, becoming light.

As Maine celebrates its bicentennial, it seems prudent to recall the state’s historical relationship with Indigenous peoples, to acknowledge how deeply that history affects our collective present, to recognize the oppressive systems and structures that continue to define that relationship, and to make the changes required to establish a foundation for a good life for all of us going forward. Charting the way forward together requires that Indigenous voices, which have been systematically silenced and denied, be welcomed, heard, and heeded. Woli jksud-a-moo-tee-yeg, if we listen well, we may be able woli-sud-ma-nen, to hear clearly and to understand those voices el-mig-adg, as time goes on.

We are collectively called upon to carefully examine the social, cultural, economic, and political underpinnings of tribal-state relations and to bring them into the light. It is a monumental task, which feels daunting to me as an Indigenous scholar, both in terms of its import and its complexity. Retracing the legacy of intergenerational impacts of racism and injustice that persist for the Chqoo-waban-a-kee-hq today is not a solo journey. I feel the weight and the emotional toll of those burdens that have been carried by so many who have come before me and share them with Indigenous peoples everywhere. Even as I acknowledge and grieve the losses, I decline to let them define me. Rather, I deliberately open the door for my voice and the voiceof other Indigenous peoples to resonate and to inform a healthy, constructive path forward that honors and celebrates our common humanity.

I wish to amplify and strengthen Indigenous voices by coming in from the margins and taking that painful journey with these courageous steps, grounded in our collective responsibility to tell our truths. I will highlight select pivotal points in our history, examine the tribal-state relationship from a couple of different perspectives, and offer some thoughts about implications for the future. I invite you to consider, as we mark Maine’s bicentennial and the fortieth anniversary of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act(s), deepening our collective inquiry into how we will respond. Specifically, how will we take responsibility for recognizing and reversing deeply imbedded colonial attitudes and practices? How might we emerge with a transformative action orientation that redresses the social, cultural, economic, and political inequalities that persistently disadvantage tribes and consequently the entire state?

| Phonetic spelling | Dictionary spelling |

| Abenaki | Aponahkewiyik |

| Bes-kud-moo-kud-ee-ig | Peskotomuhkatiyik |

| Bun-wup-skew-ee-hig | Panuwapskewiyik |

| Chqoo-waban-a-kee-hq | Ckuwaponahkiyik |

| chqoo-wubg | ckuwapok |

| el-mig-adg | elomikotok |

| Gwnus-qwum-kew-ig | Qonasqamkewiyik |

| Gwnus-qwum-kook | Qonasqamkuk |

| Mdoc-mee-goog | Motahkomikuk |

| Meeg-mug | Mi’kmaq |

| Nulum-kew-ig | Nolomkewiyik |

| Schoodic | Skutik |

| Sibyig-ew-ig | Sipayikewiyik |

| we-tchqwa-bg | weckuwapok |

| Woli jksud-a-moo-tee-yeg | Woli-ciksotomuhtiyek |

| Woli-sud-ma-nen | Woli-‘sotomonen |

| Wolus-toog-wee-hig | Wolastoqiyik |

To explore the Passamaquoddy-Maliseet language further, visit the Passamaquoddy-Maliseet Language Portal (https://pmportal.org/).

WHO WE ARE AND WHERE WE COME FROM

The places where we traditionally hunted, fished, planted, and gathered along watersheds define our communities today. We are Sibyig-ew-ig, people of the river, Nulum-kew-ig people upriver, and Gwnus-qwum-kew-ig, people of the sandy point, known collectively as Bes-kud-moo-kudee-ig, people of the pollack. We are the present-day Passamaquoddy Tribe with communities in Maine at Sibyig/Pleasant Point and Mdoc-mee-goog/Indian Township and in New Brunswick at Gwnus-qwum-kook/St Andrews. Before the United States and Canada came into being, Wolus-toog-wee-hig/Maliseet, people of the beautiful river, were part of our language family, now known as Passamaquoddy-Maliseet, two closely related dialects. Meeg-mug/Micmac, our relatives to the east, are closely related linguistically as are the Bun-wup-skew-ee-hig/Penobscot, the people who live where the river flows over the rocks, and the Abenaki to the west. Collectively we are Chqoo-waban-a-kee-hq, People of the First Light.

Passamaquoddy homelands today extend up and down both sides of the Maine/Canadian border and inland along the Schoodic/St. Croix watershed with scattered recovered land holdings in central and western Maine. The Passamaquoddy, who, with other Chqoo-waban-a-kee-hq, helped secure the border of the present day United States during the Revolutionary War, have a long-standing relationship with the federal government, formalized in the Treaty of Watertown in 1776, the first Treaty of Peace and Friendship negotiated by the United States following its Declaration of Independence. The Maine Legislature acknowledged the “significance and importance of this treaty” in a joint resolution in 2013.2

The Passamaquoddy and Penobscot tribes of Maine, who first re-established formal relationships with the federal government in 1976, have a deep intervening history with the states of Maine and Massachusetts. We focus here on the experiences of the Passamaquoddy in the United States, with home communities at Sibyig/Pleasant Point and Mdoc-mee-goog/Indian Township and tribal members who live and work throughout the state and beyond.

DEFINING FEATURES OF OUR HISTORY WITH MAINE

Commitments to Tribes by the Newly Constituted State of Maine

When Maine separated from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1820, its constitution provided that the newly formed state would be responsible for previous agreements between Massachusetts and Passamaquoddy and Penobscot Tribes, whose territories had been already been significantly reduced by unauthorized takings. Specifically, Maine accepts responsibility for honoring the treaty obligations of Massachusetts:

Fifth. The new State shall, as soon as the necessary arrangements can be made for that purpose, assume and perform all the duties and obligations of this Commonwealth, towards the Indians within said District of Maine, whether the same arise from treaties, or otherwise; and for this purpose shall obtain the assent of said Indians, and their release to this Commonwealth of claims and stipulations arising under the treaty at present existing between the said Commonwealth and said Indians. (emphasis added)3

Mysteriously, in 1875, an amendment removed this section from any printed version of the Maine Constitution, while providing that the section would remain in force. Thus, the state’s foundational agreement to honor treaty-derived obligations to the tribes, as a condition of statehood, was erased from all printed documents.

In 2015, LD893, “Resolve, Directing the Secretary of State, Maine State Library and Law and Legislative Reference Library to Make the Articles of Separation of Maine from Massachusetts More Prominently Available to Educators and the Inquiring Public,” was passed over the governor’s veto. The reference to treaty obligations was once again fully redacted from the original proposed legislation titled “RESOLUTION, Proposing an Amendment to Article X of the Constitution of Maine Regarding the Publication of Maine Indian Treaty Obligations” and changed into a narrower directive to make this information more available through the state library. The new law in its entirety reads:

That the Secretary of State, Maine State Library and Law and Legislative Reference Library, within existing resources, shall make the Articles of Separation of Maine from Massachusetts, including the fifth subsection, more prominently available to educators and to the inquiring public.4

Thus, the goal of making the treaty language more explicit and available was subverted in favor of invisibility, leaving one to wonder why the only reference to Indians in the Maine Constitution remains so carefully secreted. You might consider this omission emblematic of the politics of erasure that continues to haunt the tribal-state relationship, consistently providing cover for unjust and exploitative policies and practices that systematically oppress and deny the rights of Indigenous peoples and communities to live peaceably and thrive in their own homelands.

The persistent lack of interest in owning the state’s treaty obligations, or any obligations to fair and just dealings with tribes, beginning in the earliest days of Maine’s statehood, presaged the state’s sanction of the active exploitation of tribal resources as a matter of course. Chief William Nicholas, Passamaquoddy Tribe at Mdocmeegoog, recently testified to a twentieth-century example of unilateral state intervention that irreparably harmed the tribe:

At Indian Township, our reservation has been dramatically reduced and flooded by actions that were taken without our consent or input. In October 23, 1912: a representative of

the St. Croix paper company informed the State Governor that his company has invested several million dollars in a paper manufacturing plant and were short of power. To solve the problem, the company said that it would be necessary to flood Indian Township and to create a dam to get the necessary increase of power. The company requested support from the state of Maine, which then helped the company obtain an Act of Congress to authorize the dam being built at Grand Falls. The dam was built across the west branch of the St. Croix River at Grand Falls and flooded our reservation. What was once a river became an impoundment of water that still sits over thousands of acres of reservation land. This all happened without consent or even consultation with the Tribe. (Nicholas 2020a: 2)

Maine’s laws, policies, and practices built an enduring scaffold for state control of tribes that remained substantially unchallenged until the 1970s, when the tribes sued in federal court and re-established recognition of their government-to-government relationship with the United States. Even then, the state of Maine stridently denied any responsibility for reconciliation of its egregious systematic exploitation of tribal resources and the subsequent impoverishment of entire communities, refusing to provide recompense through the Settlement Acts, including the Maine Implementing Act and the federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, which explicitly extinguished the tribes’ aboriginal title. The Settlement Acts effectively relieved the state of responsibility for its complete cultural, political, social, and economic subjugation of the Indigenous peoples of Maine.

How Maine Carried Out Its Commitments

The state’s ability to ignore its original responsibilities for fair dealings with the tribes provided license for it to act with impunity, to make persistent incursions on tribal territory, and to deny the basic human rights of Indigenous people. Maine exerted broad authority and strict governance of all tribal affairs and took full control over tribal lands and resources. Submergence of our land through dams as described earlier, unauthorized takings for roads and railroads, long-term (999- year) leases to non-Native interests, and the cutting and sale of large swaths of virgin timber, all without recompense to the tribes, enriched the newly formed state and its citizens while impoverishing tribal citizens. More details of the state of the relationship between the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the state of Maine in 1887 can be found in Lewis Mitchell’s (1888) address to the Maine Legislature.

Earlier, in 1842, the Maine Supreme Court provided the rationale for the state’s overriding authority over the tribes when it declared the Indians “imbeciles” requiring “paternal control” by the state “in disregard of some at least of the abstract principles of the rights of man” and took full control of tribal territories, alienating lands and providing non-Native commercial interests with extensive state-sponsored opportunities for resource extraction (O’Toole and Tureen 1971: 2). A series of state court rulings served to reinforce the state’s growing power and influence over tribal interests.

In State v. Newell, an 1892 case involving a dispute over Passamaquoddy rights to hunt in their own territory according to their own rules and customs rather than Maine law, the court decided in favor of Maine, using the rationale that the Passamaquoddy no longer functioned as a political entity with the capacity for self-governance:

They have for many years been without a tribal organization in any political sense. They cannot make war or peace, cannot make treaties; cannot make laws; cannot punish crime; Cannot administer even civil justice among themselves….They are as completely subject to the state as any other inhabitants can be. They cannot now invoke treaties made centuries ago with Indians whose political organization was in full and acknowledged vigor. (O’Toole and Tureen 1971: 17)

To further strengthen state control, the state systematically developed a collection of “Laws Pertaining to Indians” that prescribed forms of tribal government, provided certain incentives to domesticate the tribes, and otherwise exercised control over all tribal affairs.5 The state presided over systematic resource extraction and social control, leaving little opportunity for tribes to provide for their own needs. A tribal trust fund consisting of the some of the proceeds of the state’s sale of tribal resources was used by state Indian agents to issue food vouchers and provide for minimal medical care at their discretion. The state exerted full control over tribal communities in concert with a strong Catholic missionary presence. Removal of children into foster care, systematic language oppression in the educational system, lack of safe drinking water and sufficient food, and lack of access to medical services all contributed to the persistent health inequities experienced intergenerationally by tribes.

A cascade of premature deaths due to these conditions and to deep and persistent bias in state court systems leaves a legacy of distrust and injury that will require a genuine and concerted effort to address. In a particularly disturbing incident at Sibyig in 1965, one tribal member, a World War II veteran and elder, was killed and another severely brain-injured at the hands of a party of five men from Massachusetts, only one of whom was criminally charged and subsequently acquitted in a Maine court. Challenges to the outcome of this incident have been blocked by the mysterious disappearance of all but a few of the court records (Woodard 2014). These acts of violence occurred in my lifetime, and our family and our Tribe still mourn the deaths of this man and other tribal members. We still carry the effects of the injuries perpetrated at the hands of these Massachusetts men and the legal systems that failed to hold anyone accountable.

Disputes over tribal rights to fish and hunt have proven to be a never-ending source of conflict, with the state asserting that the tribes have only the rights that the state specifically decides to give them and with the tribes insisting that they retain all aboriginal hunting and fishing rights not specifically abrogated. This conflict has persisted since Maine became a state and has become particularly adversarial regarding fishing rights. The Maine Indian Tribal State Commission’s extensive report describes how these issues played out between 1980 and 2014 (MITSC 2014).

Voting Rights

Ordinarily, the right to vote is an elemental right of citizenship, but for tribal citizens, whose full humanity has not always been acknowledged and who have multiple claims to citizenship, the extent of these rights has not always been clear. The federal Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted citizenship to all Native Americans living in the United States. The grant of citizenship should have carried with it the right to vote. The state of Maine, which specifically excluded “Indians not taxed” from voting, was one of the last states in the nation to amend its constitution to allow Indians to vote in federal elections in 1954. It was not until 1967 that tribal members could cast a vote in state elections.6 The right to vote in tribal elections varies, with the Passamaquoddy Tribe having local residency restrictions on the right of tribal citizens to vote in tribal elections.

FEDERAL RECOGNITION AND RESPONSIBILITY

In the mid-1970s, the Passamaquoddy Tribe and its members began to actively contest state control and, through a couple of successful court battles, established both the Passamaquoddy and the Penobscot tribes as federally recognized tribes entitled to the protection of the federal government, as trustees of tribal interests. These court decisions reaffirmed tribal rights far beyond those that the state had allowed the tribes to exercise. After this, the Passamaquoddy and the Penobscot began active participation in federal Indian programs and began to exert their rights to federal protection under the law, which now superseded the state’s ordinary exercise of jurisdiction over tribes. The tribes and tribal members began to prevail over the state in jurisdictional matters.

In the 1975 case Joint Tribal Council of the Passamaquoddy Tribe v. Morton, the US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit acknowledged the tribe’s right to have the federal government sue the state on their behalf by asserting that the state had illegally taken control of tribal territory in violation of the 1790 Non-Intercourse Act. The ensuing uncertainty over the legitimacy of title to nearly two-thirds of the state of Maine caused a rush to negotiate a settlement with the tribes. This settlement was brokered by attorneys and elected officials from the tribes, the federal government, and the state.

In one of the Passamaquoddy communities, a lengthy, complex settlement proposal was provided at the door upon entering the community meeting where a vote would be called to approve it. The tribal negotiating committee, which relied heavily on the judgement of the tribe’s attorney, had a nominal role in the final negotiations, which took place mostly among attorneys. The terms of the settlement hastily presented to the tribes for approval were not the terms that emerged in the laws passed at the state and federal levels, with significant impactful changes in those provisions made without tribal knowledge, some within days of congressional approval (Friederichs et al. 2017)

In particular, language was inserted stipulating that none of the federal laws pertaining to Indians passed in the future would apply to the tribes of Maine, unless those tribes were specifically mentioned in each new piece of legislation. This provision, never approved by the tribes, continues to unduly circumscribe and limit the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot from enjoying the usual rights and privileges accorded all other federally recognized tribes in the United States.

MAINE INDIAN LAND CLAIMS

In 1980, the Settlement Acts, including the Maine Implementing Act and the federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, extinguished aboriginal title to extensive tribally claimed lands, created a land acquisition fund intended to help the tribes reacquire a small portion of the aboriginal land holdings, and imposed the most restrictive tribal-state jurisdictional framework that exists in the United States. Substantial differences in the interpretation of this legislation have proven an inordinate burden on the tribes, whose resources to support sustained legal challenges are decidedly limited. A Maine state legislator recently observed:

The settlement was not a grant of new authority to the Tribes. It was a restriction of the jurisdiction they already possessed. With the Settlement, Maine moved in a dramatically different direction from the rest of the country at a time when federal policy had begun to strongly encourage and support tribal self-determination, a policy that continues to the present day….Maine has not developed an Indian policy based on government-to-government relations. The Settlement and court decisions effectively became the State’s only governing Indian policy. The State has failed to recognize the potential benefits of more harmonious and effective Tribal-State relations based on mutual respect for governmental sovereignty. The State has approached Tribal-State relations as a zero-sum game. (Talbot Ross 2020)

In the 40 years since the passage of the Settlement Acts, it has become apparent that the laws have numerous shortcomings as identified by the Maine Indian Tribal State Commission (MITSC), created by the Settlement Acts, and three tribal-state relations task forces convened by the Maine Legislature that have examined the issues. One of the primary duties of the MITSC is to “continually review the effectiveness of this Act and the social, economic and legal relationship between the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the Penobscot Nation and the State.” The MITSC has statutory authority to make reports and recommendations to the legislature, the Passamaquoddy Tribe, and the Penobscot Nation as it deems appropriate. The findings of the first Task Force on Tribal Sate Relations are specified in their 1997 report, At Loggerheads: The State of Maine and the Wabanaki. The results of the second convening can be found in the Final Report of the Tribal State Workgroup issued in 2008. Most recently the Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Implementing Act, convened in 2019, presented its findings and recommendations to the Maine

Legislature.7

Proposed LD 2904

Early in Maine’s bicentennial year, the state’s Judiciary Committee heard testimony on LD 2094, “An Act to Implement the Recommendations of the Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Implementing Act.” The task force, comprised of both state and tribal representatives, worked for six months to recommend 22 changes to the Maine Implementing Act. The task force calls for changes in these areas: alter- native dispute resolution and tribal-state collaboration and consultation, criminal jurisdiction, fish and game; land use and natural resources, taxing authority, gaming, civil jurisdiction, federal law provisions, and trust land acquisition. In forming the task force, the Maine Legislature provided that any changes in the law must be approved by the tribes affected before going into effect, as is required by the federal Settlement Act.

Restoring Good Faith by Reversing 1735B

A central part of restoring federal protections for tribes involves reversing the effect of section 1735 B under the federal settlement act. This controversial part of the settlement act provides that federal laws subsequently passed for the benefit of Indians do not apply to tribes in Maine, if the law would “affect or preempt the application of the laws of the State of Maine” unless the law “is specifically made applicable within the State of Maine.” Thus each new federal law applying to all federally recognized tribes would, by default, exclude the tribes of Maine. This provision was not agreed to by the tribes and, as mentioned earlier, was added just as the legislation was about to be passed by Congress. The Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Implementing Act found that since 1980, 151 laws pertaining to all other federally recognized tribes do not apply to the tribes of Maine due to this exception. It is hard to imagine how anyone stands to benefit from excluding the tribes of Maine from participating in the same laws and rules that apply to tribes throughout the nation. Improvements in the delivery of health care, the ability to obtain emergency disaster relief, and the exercise of criminal jurisdiction over crimes committed by Indians on tribal lands are all affected by 1735 B. A Passamaquoddy attorney cited this provision as

having been wielded as a weapon against the Tribes to blunt self-determination and self-governance time and time again. It has directly prevented federal funds from coming into Maine. It has stalled tribal efforts to clean up the environment. It has blocked efforts to make Maine citizens safer and more secure in their communities. Make no mistake: the consequences of §1735(b), whether intended or not, have been downright damaging to Maine as a whole. (Hinton 2020: 5).

Support for the legislation that would amend the Settlement Act focuses on the benefits that can be derived from having the tribes and state work together to develop tribal self-sufficiency. Sustained efforts to negotiate peaceful resolutions to tribal-state conflicts have been persistently denied in the face of the institutionalized belief that the tribes should be subservient to state control.

One of the tribal chiefs recently observed that the legislation has functioned for 40 years to reinforce centuries of exploitation and conflict and to suppress efforts by tribes to improve the safety and the quality of life for their citizens. Yet, in an effort to create a mutually beneficial and more harmonious relationship, he offered this perspective:

We are not here to fight about the past, we are here to fight for the future of our people and our environment. To do so, we have asked for the rights, privileges benefits, and immunities enjoyed by other federally recognized Tribes across this Nation. This is a lot to ask but it is not too much to ask. Tribes and states around the country work hand in hand every single day to improve their relations under a federal Indian law framework. There is no reason this cannot happen in Maine. (Nicholas 2020b: 4)

The proposed amendments to the Settlement Act provide for the development of an alternative dispute-resolution framework referred to as the Bicentennial Accord, which would incorporate best practices employed throughout Indian country to develop effective, productive governing principles to guide a more cooperative approach to improving tribal-state relationships. This proactive stance promises to set a tone in which the tribes and the state can work together to improve the prospects for everyone.

GOVERNMENTAL POLICY, HEALTH INEQUITY, AND INTERGENERATIONAL TRAUMA

Institutionalized efforts to subjugate and eradicate tribes through state and federal policy are implicated in persistent health inequities experienced by Native peoples. For example, the widespread practice of forcibly removing children from their families and communities into foster care and remote boarding schools has had a devastating effect on the Wabanaki and other Indigenous communities. The traumatic loss of family and cultural connections has intergenerational consequences still reverberating today. In 2013, long-time issues with enforcement of the federal Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, a federal Indian policy designed to reverse the damage, led to the convening of the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). For two years, the TRC investigated and chronicled the forcible removal of Native children into foster care in Maine and the abusive and neglectful treatment they experienced. In June 2015, the TRC released its report, Beyond the Mandate: Continuing the Conversation, reporting these central findings among others:

From our perspective, to improve Native child welfare, Maine and the tribes must continue to confront:

- Underlying racism still at work in state institutions and the public

- Ongoing impact of historical trauma, also known as intergenerational trauma, on Wabanaki people that influences the well-being of individuals and communities

- Differing interpretations of tribal sovereignty and jurisdiction that make encounters between the tribes and the state contentious

We further assert that these conditions and the fact of disproportionate entry into care can be held within the context of continued cultural genocide, as defined by the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948. (TRC 2015: 8)

Detailed findings include an acknowledgement that Native children, when they are identified, continue to enter foster care at disproportionate rates; that challenges persist in the proper implementation of the Indian Child Welfare Act; that systemic support for well-functioning Native-centered foster care systems is lacking; and that support must be made available for intergenerational healing from the traumatic experiences of those who have been affected by these systems. Recommendations include supporting cultural resurgence and ceremonial approaches to traditional healing and language restoration; honoring tribal sovereignty; and building training and system supports for encouraging strong cultural ties as well as monitoring compliance with ICWA. Maine Wabanaki REACH (Restoration-Engagement-Advocacy-Change-Healing), a nonprofit organization that initiated the work of the TRC, continues to advance “Wabanaki self-determination by strengthening the cultural, spiritual and physical well-being of Native people in Maine.”8

ADDRESSING TRIBAL HEALTH DISPARITIES IN MAINE

The complex legal and historical relationships between tribes and state and federal governments in the United States underpin and circumscribe our capacity to effectively address persistent tribal health inequities. In 2014, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Public Health Law Research project, I conducted a single-case-study research project investigating how the quality of the tribal-state relationship in Maine and the socially constructed legal environment within which it operates affect the development of law and policy to improve tribal health.9 I focused on learning how the Passamaquoddy Tribe acts through two formal tribal-state structures—the MITSC and the tribal representative to the Maine Legislature—to address tribal health issues. I specifically examined the development and disposition of the Resolve to Direct Action on Health Disparities of the Passamaquoddy Tribe and Washington County (HP0848, LD 1228) passed in 2009.10

Mediating factors that affect the tribal-state relationship were identified and recommendations to strengthen tribal- state relations to more effectively address tribal health issues were provided. The data to inform the study results included 22 in-depth semistructured key informant interviews, documentary evidence, and observation of select state and tribal governmental processes. Interviewee affiliations and roles are summarized in Table 1.

| No. | Participant affiliations |

| 12 | Passamaquoddy |

| 6 | Non-Native |

| 4 | Other tribe |

| No. | Participant primary roles |

| 4 | MITSC commissioner |

| 3 | MITSC chair |

| 3 | Tribal representative to Maine Legislature |

| 3 | Other elected tribal leader |

| 2 | Maine state legislator |

| 7 | Executive/professional staff-MITSC, state, or tribal |

In brief, the thematic analysis of the data reveals two important mediators of policy outcomes: the quality of the tribal-state relationship and the socially constructed legal environment in which this relationship is situated. A cooperative orientation to working together; deepening understanding and demonstrating respect, regular communication between the parties, attention to a constructive process and accountability for results, and institutionalization are identified as important aspects of the quality of the tribal state relationships that affect policy development and implementation. Aspects of the socially constructed legal environment in which the tribal-state relationship operates include the history of tribal-state relations characterized by colonization and dependency; the state’s tendency to resolve conflicts through enforcement and adjudication as opposed to the tribes’ persistent diplomatic efforts; personal and institutional racism; distrust; threats of violence; and a zero-sum perception, driven by poverty, racism, and competition for scarce resources, where any form of tribal benefit is seen as a loss to everyone else.

As for the resolve to direct action on health disparities, the study it required was never done, and no action plan was developed for the legislature to consider. The institutional structures currently in place, the MITSC and the tribal representative to the Maine Legislature, are inadequate, as currently constructed, to the task of addressing tribal health disparities, even when it is an urgent matter and the intention to do so is explicitly stated. It seems apparent that significant structural change will be required to improve tribal-state relationships and the capacity of the tribes to address health inequities through the state’s legislative process.

RECONSTITUTING SYSTEMS

Cultural grounding consistent with the instructions embedded in Indigenous languages, structural reordering, and economic and environmental stability are essential elements of healthy, sustainable Indigenous communities. These elements do not operate in isolation, but rather synergistically support the development and sustenance of strong tribal communities, capable of building and maintaining healthy relationships and providing for the health and longevity of the people.

Our Native languages provide the foundation for the restoration of the healthy family, social, and environmental systems that have been disrupted by persistent colonial incursions and abuses. Re-establishing the primacy of Indigenous languages as the framework upon which social systems and internal tribal structures are rebuilt is essential to cultural survival and central to tribal self-determination. The current intergenerational resurgence of efforts to create and nurture Native-speaking communities is reflective of our collective realization that the healing properties of the language are available to help us reorder and restructure our relationships to support the rebuilding of strong Native Nations. We are called upon to critically evaluate and reconstitute decision-making processes at every level in tribal, state, and federal governments. Structural reordering will be required to develop a framework for respectful, productive, healthy, and enduring tribal-state relations and an environment in which we all can thrive.

Strong self-governance processes, in which Native communities reclaim responsibility for the integrity of their own governmental systems and for implementing health-restorative policy for all the people, will serve to strengthen collective agency and build self-sufficiency. The exercise of tribal sovereignty requires consistently taking action to self-govern. Having that authority recognized by others is essential. Here in Maine, we still

have a long way to go to create an environment in which tribal communities can rebuild and reconstitute as strong Native Nations, coexisting peacefully with all of the people of the state. Building tribal sovereignty by strengthening tribal systems reverses the powerful effects of colonialism. Success in meeting tribal social and economic goals depends on the exercise of tribal sovereignty through the development of strong tribal governments, that are driven by Indigenous teachings embedded in our languages, so that they can be depended upon to act with integrity in consistently upholding collective tribal interests as the paramount concern.

Sustenance, and a safe and secure homeland, in concert with the restoration of strong tribal community relationships provide the foundation for sustainable self-sufficient communities, whose decision-making is guided by Indigenous knowledge and whose economies are directly tied to our collective health. The elimination of Native health inequities depends on restoring economic, social, political, and cultural strength to tribal communities, thus specifically reversing the effects of colonization by choosing to have Indigenous values consciously drive every decision.

THE POWER AND POLITICS OF MISBEHAVING

When appointed to certain positions, such as the Maine Indian Tribal State Commission, a nomination by the governor and confirmation by the Maine Legislature results in an authorization to serve in that capacity for a full term, “if you so behave yourself well in that office.” As a Native person, having witnessed and experienced persistent misbehavior by the state against Indigenous communities, I have often wondered how to interrupt the destructive power of oppressive state policies and create a supportive, generative environment in which we all can thrive. To do so may require some misbehaving.

Indigenous people continue to experience persistent collective health inequities rooted in the laws and policies that govern the social, political, and economic order. Peaceful and productive state-tribal relations depend on the dismantling of the colonial legacy of oppressive and exploitative law and policy. While initiatives such as the declaration of an Indigenous Peoples Day and the outlawing of Indian mascots in Maine make progress towards a cultural shift in which Indigenous peoples are respected and honored, those symbolic overtures must be backed by a systematic rebalancing of the power equation that interrupts the persistent expectation of subservience in favor of equality and partnership. The tribes and the state share responsibility for disrupting and equalizing the power relationship. The levers for social change imbedded in the policy-making process provide opportunities for civic engagement and the pursuit of social justice. In order to contribute to a healthier society, we must carefully examine our assumptions about each other and the systems within which we operate and consider accepting responsibility for acting on what we learn.

This healing journey extends to the relationships between the Indigenous peoples of Maine and others who call Maine home. Listening deeply to Indigenous voices, which have been systematically suppressed, and finding pathways to reconciliation is the work of the next 200 years and beyond. By doing so, Maine can progress in new and perhaps unfamiliar ways, working in partnership with Indigenous people to rebuild healthy communities and bring us all into the light.

Notes

1 Passamaquoddy words appear in the text in their phonetic spelling followed by English translations; see the sidebar on page 8 for the spelling used in the writing system that appears in the Passamaquoddy-Maliseet Dictionary and its companion website (https://pmportal.org/).

2 Maine 126th Legislature, Joint Resolution Acknowledging the Treaty of Watertown of 1776 on the Occasion of President George Washington’s Birthday, HP395, 2013. https://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/bills/bills_126th/billtexts/HP039501.asp

3 Maine Constitution, Article X, § 5 is available on the following website: https://legislature.maine.gov/lawlibrary/sections-of-the-maine-constitution-omitted-from-printing/9296/

4 Text of LD 893, 127th Legislature (2015) is available here: http://legislature.maine.gov/legis/bills/getPDF.asp?paper=HP0612&item=6&snum=127.

5 Maine State Dept. of Indian Affairs, “A Compilation of Laws Pertaining to Indians, State of Maine,” 1973. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED076281.pdf

6 http://archive.abbemuseum.org/headline-news/Settlement%20Act/HeadlineNewsSettlementAct.html

7 These and other reports and links can be found on the MITSC website (https://www.mitsc.org/reports-1).

8 http://www.mainewabanakireach.org/about

9 The results of this study, published here for the first time, were formally presented in 2014 to the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission, the National Congress of American Indians Tribal Leader/Scholar Forum, the Public Health Law Research Annual Meeting, and the American Public Health Association.

10 More information about HP0848, LD 1228 can be found on this website: http://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/bills/display_ps.asp?ld=1228&PID=1456&snum=124.

References

Dana, Elizabeth. 2020. “Testimony in Support of LD 2094: An Act to Implement the Recommendations of the Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement Implementing Act.” Hearing on LD 2094 Before the Judiciary Committee, 129th Legislature. Augusta, ME. http://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/bills/getTestimonyDoc.asp?id=141201

Friederichs, Nicole, Amy Van Zyl-Chavarro, and Kate Bertino. 2017. The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act: Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations. Commissioned by the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission. https://digitalmaine.com/mitsc_docs/24/

Hinton, Corey. 2020. “Testimony in Support of LD 2094: An Act to Implement the Recommendations of the Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement Implementing Act.” Hearing on LD 2094 Before the Judiciary Committee, 129th Legislature. Augusta, ME. http://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/bills/getTestimonyDoc.asp?id=141202

Mitchell, Lewis. 1888. “Address to the Sixty-third Legislature.” Maine State Legislature, House Document no. 251. Augusta, ME: Burleigh and Flynt. http://www.wabanaki.com/wabanaki_new/documents/Mitchell%20Speech%201887%20(official%20reduced).pdf

MITSC (Maine Indian Tribal State Commission). 2014. Special Report Assessment of the Intergovernmental Saltwater Fisheries Conflict between the Passamaquoddy and the State of Maine. Trescott, ME: MITSC. https://www.mitsc.org/reports-1

Nicholas, William. 2020a. “Testimony in Support of LD 2094: An Act to Implement the Recommendations of the Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement Implementing Act.”Hearing on LD 2094 Before the Judiciary Committee, 129th Legislature. Augusta, ME. http://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/bills/getTestimonyDoc.asp?id=141137

Nicholas, William. 2020b. “Testimony in Support of LD 2094: An Act to Implement the Recommendations of the Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement Implementing Act. http://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/bills/getTestimonyDoc.asp?id=141200

O’Toole, Francis J. and Thomas N. Tureen. 1971. “State Power and the Passamaquoddy Tribe: ‘A Gross National Hypocrisy?’” 23 Maine Law Review 1.

Talbot Ross, Rachel. 2020. “Testimony in Support of LD 2094: An Act to Implement the Recommendations of the Task Force on Changes to the Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement Implementing Act.” Hearing on LD 2094 Before the Judiciary Committee, 129th Legislature. Augusta, ME. http://www.mainelegislature.org/legis/bills/getTestimonyDoc.asp?id=139833

TRC (Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth & Reconciliation Commission). 2015. Beyond the Mandate: Continuing the Conversation. http://www.mainewabanakireach.org/maine_wabanaki_state_child_welfare_truth_and_reconciliation_commission

Woodard, Colin. 2014. “Family’s Quest for Justice Still Burns, 50 Years Later.” Maine Sunday Telegram, August 3, 2014. https://www.pressherald.com/2014/08/03/epilogue-fire-still-burns-for-familys-half-century-quest-for-justice/

Gail Dana-Sacco became the first known Passamaquoddy to earn a Ph.D. when she completed her doctorate in health policy and management at Johns Hopkins University in 2009. Today, her work centers on advancing wolibmowsawogon, a world in which Indigenous peoples, lands, and languages can thrive. This article is dedicated to all the Passamaquoddy who have come before us and who are with us today, and the

ones who are still to come, whose love and support have made this journey possible and will guide us forward. Gazelmulpa.